Werkstattkino München

14. — 20. März 2019

Gina Kim 김진아 ist eine vielseitige Filmemacherin und Künstlerin: Ihr Werk umfasst ein breites Spektrum vom experimentellen Tagebuchfilm über VR Produktionen und Videoinstallationen bis zu großen Spielfilmen.1973 in Südkorea geboren, ging Gina Kim mit 22 Jahren in die USA, um am California Art Institute in Los Angeles u.a. bei James Benning und Hartmut Bitomsky Film und Medienkunst zu studieren. Das Videotagebuch, das sie 1995 bis 2000 führte, bildete die Materialgrundlage für ihren ersten Langfilm GINA KIM’S VIDEO DIARY, in dem sie ihre von Isolation und Essstörungen geprägte erste Zeit in den USA künstlerisch verarbeitete. Die darauf folgenden fiktionalen Arbeiten INVISIBLE LIGHT und NEVER FOREVER erforschen die Identität von Frauen in der koreanischen Diaspora und ihr Verhältnis zu ihren Sehnsüchten. Die Reihe im Werkstattkino zeigt alle drei Filme als Münchner Erstaufführungen.

Präsentiert wird das Programm von Susanne Mi-Son Quester, die außerdem einen ihrer eigenen Filme vorstellen wird. Den Dokumentarfilm PAJU — DIE INNERE TEILUNG drehte sie an der Grenze zwischen Nord- und Südkorea. Neben Begegnungen mit den Anwohnern dieser Grenze erzählt der Film auch von der Familiengeschichte der Autorin, deren Großeltern von Nord- nach Südkorea geflohen sind. Susanne Mi-Son Quester ist bei den Vorführungen anwesend und wird Fragen zu den Filmen beantworten.

Programm, Redaktion und Texte: Susanne Mi-Son Quester. Gestaltung: Florian Geierstanger. Vielen Dank an Gina Kim, Christoph Schwarz, Barbara Westphal, Johanna Pauline Maier und Bernd Brehmer

Filme

Gina Kim’s Video Diary

김진아의 비디오 일기

153min, DVD/Digibeta, ROK/USA 2002 Buch, Regie und Schnitt: Gina Kim. Koreanisch und Englisch mit englischen Untertiteln

Eine junges koreanisches Mädchen verlässt ihr Elternhaus und geht zum Studium nach Amerika. Scheinbar frei von äußeren Zwängen dokumentiert sie mit ihrer Videokamera sich und ihren Alltag und gerät dabei in eine seelische Krise.

Mit ruhigen und doch schockierenden Bildern ermöglicht das Werk im Zuge der Beobachtung einer Frau eine ungewöhnliche Erfahrung, die sich deutlich von den Ansätzen konventioneller Medien unterscheidet. Die behutsame Auswahl der Einstellungen macht diesen extrem persönlichen Bericht einer Frau über ihre Ängste, Phantasien und Pläne für den Zuschauer zu einem außerordentlichen, lebensbejahenden Selbstporträt, das tief bewegt.

Berlinale Forum

Donnerstag, 14.3.2019, 20:00 Uhr

Montag, 18.3.2019, 20:00 Uhr

Invisible Light

그집앞

78min, 35mm, USA/ROK 2003 Buch und Regie: Gina Kim, Kamera: Peter Gray, Benito Strangio, Darsteller: Sun-jin Lee, Yoon sun Choi. Koreanisch mit englischen Untertiteln

INVISIBLE LIGHT erzählt hintereinander die Geschichten von zwei koreanischen Frauen: Gah-In (Sun-jin Lee) ist die Geliebte eines verheirateten Mannes und Do-Hee (Yoon sun Choi) seine Ehefrau. Diese erwartet ein Kind von einem anderen Mann und flüchtet nach Korea, um sich zu entscheiden, ob sie das Kind abtreibt − oder nicht.

Mit außergewöhnlicher Schönheit bringt INVISIBLE LIGHT Elemente aus Kims Videoarbeit (Essstörungen, den Kampf um eine unabhängige Persönlichkeit) und einer Arthouse-Tradition von Filmen über Charaktere in psychologischen Extremsituationen zusammen. Er fügt dem aufstrebenden koreanischen Frauenkino neue Verstrebungen und Kräfte hinzu.

Tony Raynes, Vancouver Film Festival

Freitag, 15.3.2019, 20:00 Uhr

Dienstag, 19.3.2019, 20:00 Uhr

Never Forever

두번째 사랑

104min, 35mm, ROK/USA 2007 Buch und Regie: Gina Kim, Kamera (Technicolor): Matthew Clark, Darsteller: Vera Farmiga, Jung-Woo Ha, David L. McInnis Englische Originalversion

Sophie (Vera Farmiga) und ihr koreanischstämmiger Mann Andrew (David L. McInnis) scheinen eine perfekte Ehe zu führen − wären sie nicht kinderlos. Um die Beziehung zu retten, trifft Sophie eine Vereinbarung mit dem illegalen koreanischen Einwanderer Jihah (Jung-Woo Ha): für ein festgelegtes Honorar soll er ihr ein Kind zeugen.

Kim kreiert den perfekten Ton bis hin zu einem Klima der extremen Repression, in dem die sexuelle Energie fast zu brennen beginnt. Vera Farmigas unglaublicher Auftritt als Sophie ist ein wahres Geschenk. Als perfektes Gegenstück zu zwei begabten männlichen Hauptdarstellern macht ihre meisterhafte Darstellung von Sophies gradueller Veränderung NEVER FOREVER zu einer unvergesslichen Kinoerfahrung.

John Cooper, Sundance Film Festival

Samstag, 16.3.2019, 20:00 Uhr

Mittwoch, 20.3.2019, 20:00 Uhr

PAJU — Die innere Teilung

파주

78 Minuten, HD, D 2019 Buch und Regie: Susanne Mi-Son Quester, Kamera: Mieko Azuma. Koreanisch und Deutsch mit deutschen Untertiteln

Eine deutsch-koreanische Filmemacherin reist an die Grenze zwischen Nord- und Südkorea und begegnet den Bewohnern der Stadt Paju und ihren unterschiedlichen Beziehungen zur Teilung des Landes. Neben der äußeren wird dabei auch eine innere Teilung sichtbar: zwischen den Generationen, ihren Erfahrungen und ihren Wünschen für die Zukunft.

Die Wahl der Gesprächspartner und die Interviewführung sind die großen Trümpfe des undogmatischen Films, der menschliche Nähe zu den gewählten Protagonisten schafft. PAJU — DIE INNERE TEILUNG ist ein kluger, reflektierter und doch auch sehr persönlicher Dokumentarfilm über ein geteiltes Land.

Jurybegründung der Deutschen Film- und Medienbewertung

Sonntag, 17.3.2019, 20:00 Uhr, in Anwesenheit der Regisseurin, Moderation: Bert Rebhandl

Montag, 18.3.2019, 18:00 Uhr, in Anwesenheit der Regisseurin

Interview with Gina Kim

Susanne Quester: The video source for GINA KIM’S VIDEO DIARY was shot over a long time and you edited several short films prior to the long diary version. Can you tell more about the process?

Gina Kim : I discovered the video medium as a senior in college and was struck by its potential for the ‘democratization’ of art – the possibility of mass production that makes art accessible for the mass public. I started keeping a video diary nearly every day, which generated to hundreds of hours of footage from 1995 to 2000. At first I kept the video diary in order to comfort myself, not intending to show it to anyone. But soon I realized what I was doing was something meaningful. In the (paper) journal I kept in 1996, I wrote „I don’t know what exactly it means to pursue this, but I am doing it because I know it will mean something to someone someday. I know in my gut that my struggle is not limited to myself. It is about a young woman who didn’t have voice in this post-colonial male-centric world. Maybe someday, someone will be able to tell me what these images all mean.“

Susanne Quester: I am particularly interested in the editing process – was there anybody supporting you?

Gina Kim: As I mentioned above, I decided to edit the massive amount of footage so that I could put it out in the world. But the editing process was long and excruciating. After watching the footage repeatedly, I first had to figure out a big story- a ’narrative‘ if you will – from the amassed footage. Then I went through each tape to decide what to keep and what to leave out. It took me nearly two years to edit it since I sometimes had to stop to distance myself from it. When I felt lost and frustrated, I would show bits and parts of the footage to my mentors and friends to get feedback. But all in all, it was a solitary process. I came to terms with the issues I struggled with and successfully became an adult woman through the editing process, as much as through shooting the footage.

Susanne Quester: Are you still keeping a video diary or when and why did you stop?

Gina Kim: I stopped keeping a video diary in 2000. Throughout the editing process, I became gradually disinterested in keeping a video journal. I was much more interested in interpreting the images I already compiled as if I was my own subject of psycho-analysis. More importantly, I had another creative outlet that occupied me by then. As I edited the footage, certain cryptic images kept popping into my head. Intrigued, I started jotting the images down in a big notebook. The images mostly featured two solitary women in spaces – one in Korea and the other in California. The images were seemingly random but somehow mysteriously coherent. It was as though I had a million pieces of a puzzle in my mind and I was playing with them, not knowing what to do with them. By the time I finished editing GKVD, my notebook was completely filled with my notes. When I connected the missing dots and figured out how to put them into a big picture, I realized two women had been born in my notebook. Those two women became the main characters of INVISIBLE LIGHT.

Susanne Quester: INVISIBLE LIGHT is divided into two parts, showing the two female characters completely isolated from each other. What was the idea behind this concept? What do the two women have in common?

Gina Kim: On thematic level, they both cannot make peace with their own bodies and desires. The two women intentionally misplace themselves in the world geographically, in order to give themselves an opportunity to figure out what they really want, and each suffers from intense isolation as a consequence. In terms of the story and character, they have one man in common – Gah-in’s lover who is also Dohee’s husband. I wanted to make sure that the man is absent in the film. He connects the two women but the film is not about him. The story is about the two women.

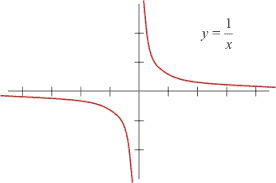

When I was conceiving the film and writing the script, I kept thinking about a mathematical function Y=1/X (see below) The graph you get from that function is not one, but two beautiful curves – one in ++ arena and the other in – – arena. I put the man in the center of the graph ( which is 0 ) and built and shaped the story of these two women based on this mathematical function.

As the graph suggests, the two women in INVISIBLE LIGHT are mirror images of each other. Gah-in (in Chinese characters, it means house + person) is someone who never leaves her home in LA. She is an international student from Korea and has an affair with a married man. She is disgusted by her own behavior and punishes herself by locking up and starving herself. Dohee (in Chinese characters, it means street + person) lives in the US but leaves for Korea when she finds out her husband is having an affair with Gah-in. She expresses her anger by sleeping around, which leads her to unwanted pregnancy. Not being able to confront the dillemma, she wanders the streets of Seoul aimlessly.

Susanne Quester: Your next feature film, NEVER FOREVER was entirely shot in the US, starring the awesome actress Vera Farmiga. Why did you decide for a Caucasian main character?

Gina Kim: It is hard to elaborate exactly ‚why‘ I ‚decided‘ to build the story around a white woman. Stories come to me through an organic process and I simply follow my intuition. My subconscious is like an enigmatic black box that absorbs all of my surroundings and people around me. At the right moment, the black box pours out strange characters and stories that I myself don’t understand fully. I make films, write and paint in order to understand them.

When I moved to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to teach at Harvard University in 2004, I was surprised by the homogeneity in the demographics not only in the intellectual community but also in the city itself. My predominantly white colleagues and students were truly wonderful and I didn’t suffer from any racial discrimination. Nonetheless, I felt a strange sense of isolation every time I found out that I was the only Asian or even person of color in the room everywhere I went – libraries, movies theaters and conference rooms.

At the same time, I was teaching a course on Korean cinema (offered for the first time in an Ivy League university) and had awesome opportunity to revisit all the classic Korean melodramas from the 50s and 60s. I was shocked by the subversive nature of the female characters ( in those films ) who, sadly, are compromised and punished at the end of each film for having their own desires. Then, little by little, the small vignettes and characters that ended up in NEVER FOREVER emerged from all of these experiences. I believe the three of the main characters in the film (Jihah, Andrew and Sophie) symbolize the three different kinds of people that reside in the US in terms of racial, ethnic and national diversity. But it is also possible I wanted to divide and project myself evenly into three characters. Jihah – an immigrant worker from Korea, Andrew – a successful Asian American who made it into the mainstream society in the US, and Sophie – a highly repressed white woman who is unable to figure out what she wants. Maybe I wanted to balance among these three characters and put a bit of distance between Sophie and myself by making her white.

Susanne Quester: You chose ‚Desire & Diaspora‘ as title for this retrospective – what is the meaning of these terms for you and your cinematic work?

Gina Kim: Desire and Diaspora are two key words that can describe my works as well as my life. The current world tends to operate on false dichotomies: man/woman, west/east, foreigner/native, human/nature, people of color/white etc. Although the world has become much more complicated, our semiotic consciousness hasn’t evolved beyond the dichotomy. And the false dichotomy inevitably creates a boundary and the boundary divides the world as people within the boundary (we) and outside of the boundary (others/they). Once set, it is hard to cross these boundaries. What’s interesting is desire creates a potent agency that challenges such taboos and boundaries. The boundary never entirely disappears because that’s not how the current world operates, but with desire, you become a nomadic being that doesn’t belong either side of the boundary. Then diaspora is created. As a Korean living in the US, I’ve accepted and embraced the status of my nomadic state of my being at this point – but it leaves me with an existential melancholia and intense nostalgia. For the things that you left behind. For the things that now you lost. That’s diapora. All of my works are in a way an attempt to process these affects and thoughts.

Gina Kim and I

Von Susanne Mi-Son Quester

In einem Seminar von Gerhard Friedl sah ich 2003 zum ersten Mal GINA KIM’S VIDEO DIARY. Der Film hinterließ einen tiefen Eindruck bei mir. Fast schmerzhaft unvermittelt verwendete eine junge Frau hier die Kamera, um ihre Gedanken, Sehnsüchte und Ängste aufzuzeichnen. Manche Bilder sind mir über die Jahre in Erinnerung geblieben: der Schatten der Jalousien, das Köpfen einer Makrele oder das Ausbluten eines Teebeutels.

Im Sommer 2004 kaufte ich mir meine erste Videokamera und reiste für einen einjährigen Studienaufenthalt nach Südkorea. In der neuen Umgebung angekommen drehte ich große Mengen Videomaterial, auch von mir selbst. Dieses Material zu einem Film zu schneiden, fiel mir jedoch schwer. Es entstanden daraus einige kürzere Arbeiten, aber der Blick auf mich selbst bereicherte mich nicht. Mit dieser Erfahrung begann ich ein neues Filmprojekt und wählte dafür die Form eines Portraits: DIENSTAG UND EIN BISSCHEN MITTWOCH beschreibt einen Tag im Leben einer 17-jährigen Schülerin in Seoul, die sich unter großem Leistungsdruck auf die Eignungsprüfung zur Kunstakademie vorbereitet. Gina Kim, die in Südkorea Kunst studiert hat, bevor sie in die USA emigrierte, hat in ihrer High School-Zeit sicher Ähnliches durchlebt.

Als ich das VIDEO DIARY im Zusammenhang mit Kims späteren Filmen wiedersah, fiel mir erst auf, wie kontrolliert sie bereits in ihrem ersten Film gearbeitet und wie geschickt sie ihr psychisch sicherlich sehr belastendes Material strukturiert hat. Gina Kim sagt, ihr sei bereits relativ früh (1996) bewusst gewesen, dass das Material eine über sie hinausweisende politische Bedeutung habe. Diese Verankerung in einem politisch-intellektuellen Diskurs ist für den Prozess sicher sehr hilfreich gewesen. Trotzdem wohnt dem Material von GINA KIM’S VIDEO DIARY auch eine zauberhafte Unmittelbarkeit inne, die sie in ihren späteren Spielfilmen nur selten wiedergefunden hat.

2014 begann ich wieder ein neues Projekt in Südkorea, PAJU — DIE INNERE TEILUNG. Für die koreanische Teilung hatte ich mich schon lange interessiert, da sie für die jüngere Geschichte und die Politik der beiden Koreas grundlegend ist. Bei meinen Recherchen im Grenzgebiet faszinierte es mich, dass die Menschen, die die Grenze direkt vor der Nase hatten, diese überhaupt nicht wahrzunehmen schienen. Mein Koreanisch hatte sich mit den Jahren verbessert, und ich entdeckte den Genuss, mit den Menschen zu sprechen, anstatt sie schweigend zu beobachten. Wenn man miteinander spricht, entsteht ein Raum, den man gemeinsam gestalten kann, während der stumm Beobachtete den Vermutungen des Filmenden fast ungeschützt ausgeliefert ist. Und so ist PAJU entgegen meiner ursprünglichen Absicht zu einem Film mit vielen Gesprächen geworden. Ich selbst komme darin zwar indirekt durch meinen Kommentar und meine Fragen im Off vor – beim Schnitt hatte ich aber den Eindruck, dass dem Film noch so etwas wie ein Körper fehlte. Versuche, mich zu filmen, hatten wir gemacht, ich hielt sie für unbrauchbar. Es fehlte ihnen die unmittelbare Lebendigkeit, die dokumentarisches Material so reizvoll machen kann. Das war der Moment, mich an mein altes koreanisches Tagebuchmaterial zu erinnern, und ich habe einige Aufnahmen daraus an den Anfang des Films gestellt. (Februar 2019)